Lombok's #1 Tourism Magazine

When travellers make the boat crossing between Bali and Lombok, they probably don’t realise they are not only crossing one of the deepest bodies of water in the world, but also crossing a transitional zone between Asia and Australia.

When travellers make the boat crossing between Bali and Lombok, they probably don’t realise they are not only crossing one of the deepest bodies of water in the world, but also crossing a transitional zone between Asia and Australia.

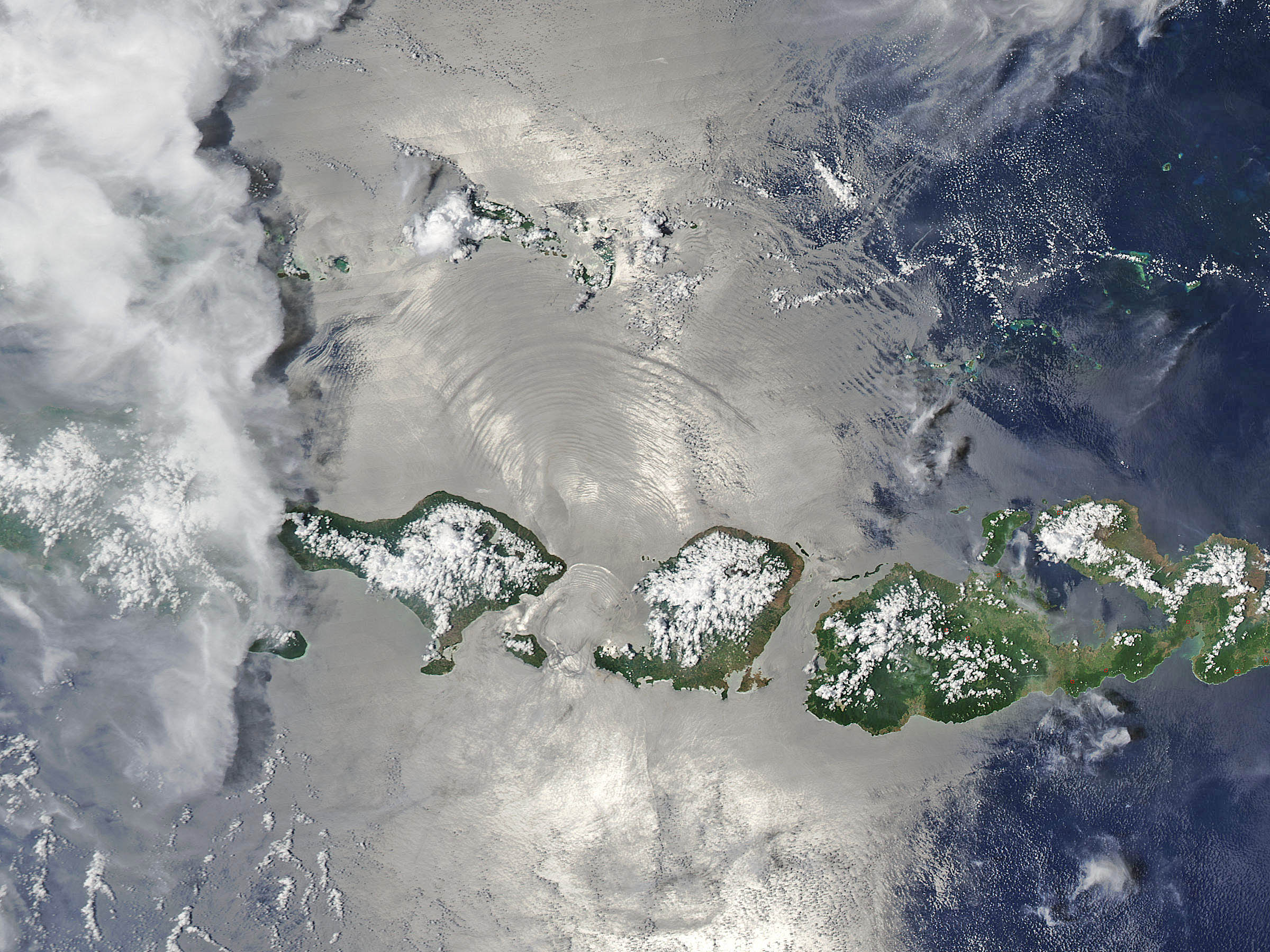

The Lombok Strait separates the islands of Bali and Lombok, and connects the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean.

At its northernmost end, the Strait has a deep channel that is about 35kms (less than 22 miles) wide and is well-known for its strong currents and north-south ‘through-flow’, which can run at several knots and is very deep.

At its northernmost end, the Strait has a deep channel that is about 35kms (less than 22 miles) wide and is well-known for its strong currents and north-south ‘through-flow’, which can run at several knots and is very deep.

At the northern end it starts with a depth of 1,500 metres and then averages around 400 metres until the southern end, where it increases again to 1,500 metres and eventually to 3,000 metres.

Tankers with large drafts and submarines regularly pass through the Strait, avoiding the much shallower and congested water of the Malacca Straits.

This channel is so important that the Japanese took control of the Lombok Strait during WWII and, in 1942, the battle of Lombok Strait took place when an American destroyer squadron engaged a large Japanese naval force.

However, most passengers who travel to Lombok or the Gilis know nothing about the other name associated with this part of the world: “The Wallace Line”.

In the second half of the 19th century, the English explorer and naturalist, Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913) spent a number of years travelling around the region, studying and documenting the human culture of the Malaysian and Indonesian islands and their flora and fauna.

In the second half of the 19th century, the English explorer and naturalist, Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913) spent a number of years travelling around the region, studying and documenting the human culture of the Malaysian and Indonesian islands and their flora and fauna.

During his years of travel, he noticed how species of animals and plants differed greatly between the islands in the western part of the Indonesian archipelago and the islands to the east.

Sulphur-crested cockatoo were found to the west, and Indonesian finches lived just across the Strait. Fire-prone gum trees grew on one side and exotic tropical rain forest on the other. Even beneath the sea, in an area separated by mere miles, there was an incredible separation of fish life.

One of Wallace’s greatest interests was to explain why this was so and much of his work revolved around the idea of “survival of the fittest”, or natural selection.

What particularly struck Wallace about his discovery was that some islands that were very far apart had the same distribution of animal species; while some islands that were close together had very different species.  Nowhere was this more striking than between the islands of Bali and Lombok, which are separated by only 35km of water.

Nowhere was this more striking than between the islands of Bali and Lombok, which are separated by only 35km of water.

Numerous species of plants and animals – especially birds – that are found on Bali and other islands to the north and west, were absent on Lombok, which had species found on other islands far to the south and east.

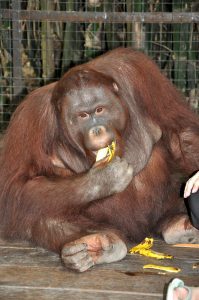

Wallace observed that there was a marked difference between the flora and fauna on either side of the line – for instance, there are tigers, rhinos and bears west of the line that do not live to the east; while there are marsupials, cockatoos, Komodo dragons and other animals that live in the east but not to the west of the line.

“Survival of the fittest” didn’t explain these differences; therefore, he concluded that ancient geological changes must have been the cause.In between constant bouts of malaria and other tropical illnesses, he finally came up with the theory of “The Wallace Line” – an invisible line that separates the world of tigers from the world of kangaroos.

“Survival of the fittest” didn’t explain these differences; therefore, he concluded that ancient geological changes must have been the cause.In between constant bouts of malaria and other tropical illnesses, he finally came up with the theory of “The Wallace Line” – an invisible line that separates the world of tigers from the world of kangaroos.

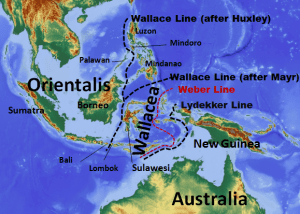

He theorised that an imaginary boundary ran from between Borneo (Kalimantan) and Sulawesi in the north, and down between Bali and Lombok in the south.

From these differences, biologists concluded that at one point the land masses of South-east Asia were connected to Australia but eventually moved apart, and the deep Lombok Strait acted as a barrier to the movement of species west across the Wallace Line.

This fundamental insight that the division between the different species must have been connected to ancient geological shifts put Wallace far ahead of his time and remains a remarkable achievement to this day.

Today this zone of transition is still called the Wallace Line and is recognised by biologists as the sharpest and most famous boundary in the world.

In honour of Wallace’s work, naturalists now refer to the area around the line as “Wallacea” and the region around the Wallace Line is considered to be amongst the most ecologically diverse in the world, alongside the Amazon Rainforest and the Congo Rainforest.

In honour of Wallace’s work, naturalists now refer to the area around the line as “Wallacea” and the region around the Wallace Line is considered to be amongst the most ecologically diverse in the world, alongside the Amazon Rainforest and the Congo Rainforest.

Wallace also has one other claim to fame. In the 1850’s he was busy formulating a theory of evolution, in parallel with the work being undertaken by Charles Darwin – a theory that was considered quite heretical at the time. Wallace first published a paper on the “introduction” of the species in 1855.

Wallace had a lot of respect for the work of Darwin and was willing to share information. Whilst working in Borneo, he sent him a manuscript, which Darwin received in June 1858.

The manuscript further advanced Wallace’s theories and may have been the spur for Darwin to ‘go public’ and publish his own work, “On the Origin of Species” in November 1859.

Wallace’s name and work will always be remembered for ‘the Line’. However, he came very close to being credited in history with the theory of evolution, too.

Thanks to Howard Singleton, who contributed sections of this article.